During the design process for this year’s Lunar New Year greeting card, hua foundation staff member christina sat down with illustrator and designer Triet Pham to reflect on his experiences celebrating the holidays growing up in Vietnam and as a student in diaspora, as well as his inspirations for this year’s card.

—

Triet Pham grew up fascinated by mythologies. This began with Egyptian and Greek mythologies, but as he grew older, and especially when he moved away from home for university, he developed a deep interest in the parts of his own Vietnamese culture that weren’t as well known: the history, the folklore, and (especially as an illustrator and designer) the visual symbolism of traditional styles of artwork.

So much of the young adult diasporic experience –whether we are raised in our homelands and move away later in life, or spend our entire lives separated from them by distance– involves deep reflection of the things that we take for granted when we are growing up. For Triet, his childhood experiences of Lunar New Year in Vietnam were marked by big communal extended family celebrations spanning multiple days, the excitement and anticipation of preparing homes for festivities, and the atmosphere of the market coming together in honouring the change of seasons.

Moving halfway around the world for school, Triet knew that the celebrations and festivities would not be the same in scale, but found himself realizing that the traditions that were so deeply tied to his identity were harder to recreate on his own than he had thought. There were many activities and rituals that he had participated in his whole childhood, but didn’t fully understand the roots of those traditions or how to carry them out on his own.

In the absence of extended family, Triet began building new traditions together with his Vietnamese roommates and found family. As young adults with busy schedules, they adapted rituals and activities to the scale of what they could reasonably pull together in the small space of their home. This meant being more intentional with their practices: while Lunar New Year is often known for its ostentatious and vibrant celebrations, sometimes simplicity can be just as meaningful. For Triet, one of his favourite new traditions is to monitor the local Vietnamese Facebook community for people selling homemade bánh chưng and bánh tét, and making the pilgrimage out to pick them up.

What does it mean to truly celebrate Lunar New Year? As we grow and adapt into new spaces, can we (re)write our own mythologies of diaspora? Mythologies are not necessarily grounded in ‘truth,’ but rather they make up the stories and beliefs that we tell ourselves to support learning, growth, and connection. What are the stories that we tell ourselves about how we got here and where we will go?

mythologies of the diasporic new year

The Lunar New Year marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, celebrating and honouring deities and ancestors, and thoughtful preparation of our homes to set the tone for the year ahead. Festivities revolve around family and community, a coming together of extended family and friends, updating each other on the past year and our plans to come, though sometimes these questions may poke deeper than we are comfortable with.

The diasporic new year is an homage to communal celebration, collectively built, but with a kindness towards ourselves to practice in ways that make sense with our livelihoods and situations. It values intention over being ‘correct’ or ‘traditional,’ with an understanding that there isn’t a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to celebrate, when you are doing so with your whole heart.

Traditionally, Lunar New Year is a community celebration, but within it is a deep grounding in personal introspection: what we wish for ourselves and how we wish to hold ourselves in community. The moral of this new mythology asks us how we build healthier relationships with culture and family, that don’t feel as if they are rooted in obligation, but rather in agency and empowerment, to hold all of the pieces of ourselves together as whole beings:

Culture is a place, and I have a right to feel safe in a place that I call home.

the design

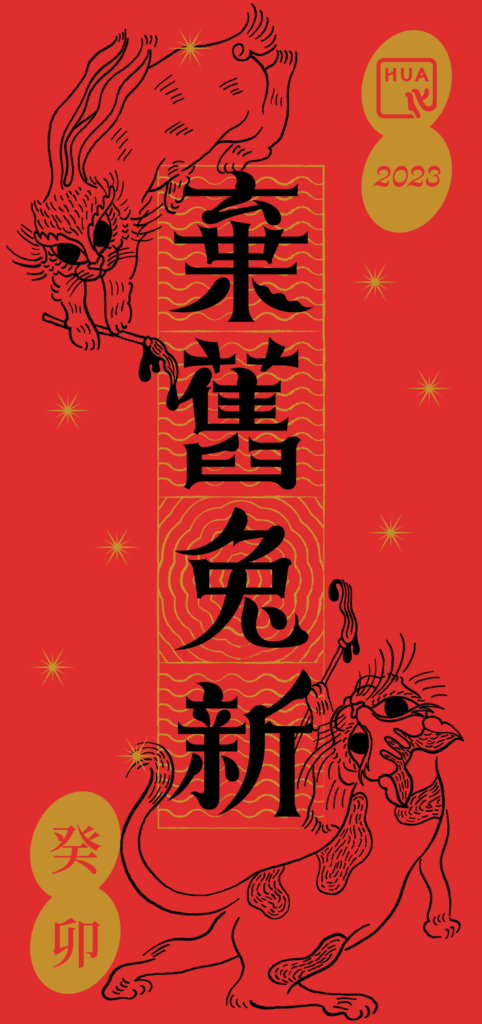

Triet’s favourite visual element of the Lunar New Year has always been calligraphy. It wasn’t something that his family ever hung up in their home, but every year he would see calligraphers at the market with their big brushes and vibrant red papers. Both the form and the meaning were intriguing: ornate manipulations of classical sayings, manifestations and prayers for the coming year. In concept, a visual representation and physical reminder of our intentions and wishes for ourselves and our loved ones. In practice, calligraphy requires deep focus, care, and intention, a parable for how we should move towards these goals and dreams.

This year’s card features a saying in four Chinese characters: 棄舊兔新 ‘to turn over a new leaf’. Traditionally, these sayings are a play on words, where the zodiac animal of the coming year replaces a similar sounding word in a classical idiom. The Rabbit replaces the word 圖, which means ‘to plan,’ ‘to map,’ or ‘to draw’ in some contexts. The design is intended to reflect this, with the animals actively engaging with the words.

In this coming change of seasons, the Vietnamese Zodiac differs from the Chinese Zodiac, where the Rabbit is replaced with the Cat. This year’s design brings these two animals together in collaboration, and with intentions of planning futures together in solidarity.

—

We currently have a limited number of hua foundation x Triet Pham Lunar New Year greeting cards for sale! Order yours now at the link below.