This piece explores the intersection of Filipino Chinese mythology and Lunar New Year traditions, with me, Nathalie De Los Santos, reflecting on the importance of reclaiming our folklore and personal history. Romeo Reyes’ art features a striking snake intertwined with soft peonies, adorned with Filipino tattoo patterns symbolizing our ancestral connection, blending the two cultures beautifully. Order your cards now and help us celebrate Romeo Reyes’ beautiful art and practice!

Each year, as the Lunar New Year approaches, we often see celebrations framed through a predominantly East Asian lens—bright red lanterns, lion dances, and auspicious greetings in Mandarin or Cantonese. But for many of us, particularly those with Filipino Chinese heritage, the holiday’s significance extends beyond these familiar images. This year, I want to spotlight Filipino Chinese mythologies and show how our communities have always celebrated in ways that merge cultural practices, ancestral reverence, and shared meals that connect our present with our roots.

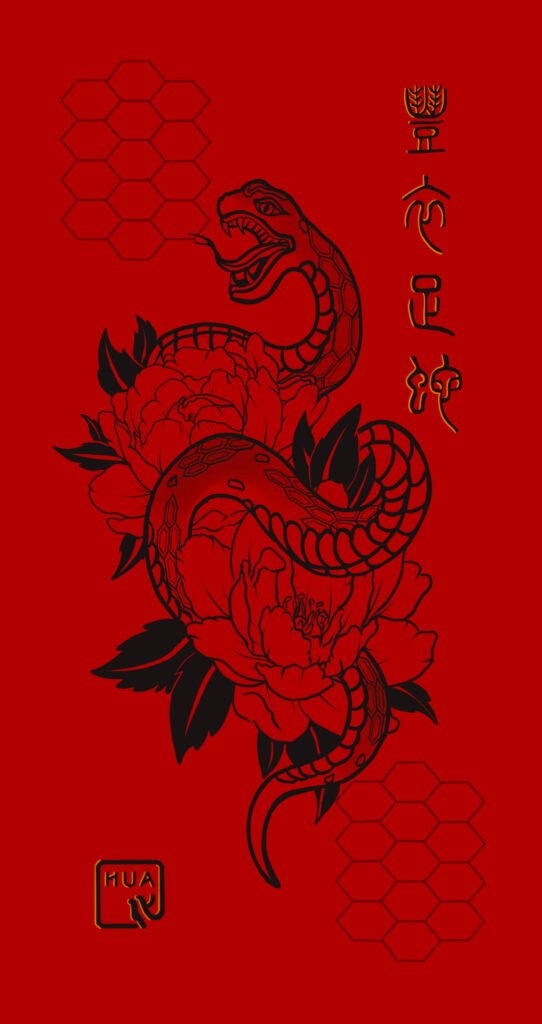

One collaboration that has helped me explore this aspect of Lunar New Year is my work with Filipino Chinese artist Romeo Reyes, who illustrated our 2025 design, featuring this year’s zodiac animal: the snake. The snake, while often misunderstood as a symbol of deceit or danger, holds a very different meaning in Filipino mythology. According to sources like Lane Wilcken’s work on Filipino tattoos, snakes can be harbingers of good fortune: if one followed you into battle, it indicated that the ancestors were on your side. Far from something to fear, the snake can be a companion of spiritual guidance, transformation, and strength.

Romeo’s artwork incorporates intricate Filipino tattoo markings—some inspired directly by Wilcken’s research—that serve as protective symbols and reminders of ancestral presence. These batok motifs are woven into the snake’s scales and echo the hexagonal patterns known as inufu-ufug by the Kalinga and the people of the Benguet region or minmináta by the Itneg, representing the many eyes of our forebears watching over us. In Chinese symbology, the hexagon can symbolize balance, unity, and harmony across the six directions—north, south, east, west, up, and down. This seamless melding of Filipino tattoo patterns with Chinese symbolism beautifully reflects the balancing act of holding multiple cultural identities.

I am, myself, a Snake-year baby, which has led me to reflect on how myths and traditions can shape our identity. Growing up, my connections to Lunar New Year involved gatherings with comforting and delicious food. Though not specific to Lunar New Year, Romeo and I both eat noodles for a long life during every birthday, which is a practice from our Chinese ancestors. Alongside these noodles, my friend Kristoffer Young, a chef and community organizer shared with me that the Filipino Chinese community also embraces the custom of eating sticky foods such as tikoy, symbolizing how a family must “stick” together in order to thrive. We also enjoy lun pia, commonly known as lumpia. This is a Chinese-influenced dish that has evolved to include Filipino, Spanish, and American influences through the use of ingredients like heart of palm, Spam, or various sauces. When we pause to savour these foods, we’re invited to the metaphorical table of our ancestors, reflecting on values and resilience taught across generations. In remembering how these dishes were created, we can continue to reinterpret and reshape traditions.

The conversations I’ve had with friends like Kristoffer and Dominique Bautista around this new artwork illuminated our intertwining identities. They observed how the snake’s fierce expression is softened by lush peonies—a flower symbolic of prosperity and good fortune in Chinese culture—and how that contrast can speak to the duality we often embody in the diaspora: gentle yet strong, beautiful yet fierce, deeply rooted in traditions while forging new paths. This balance is reminiscent of how we navigate old practices in new settings, shaping our own ceremonies in faraway lands, yet always honouring where we came from.

Being Filipino Chinese means constantly negotiating multiple cultural identities, further complicated by my Spanish, Japanese, and Canadian connections. My Filipino ancestors lived in Luzon and Cebu, and my Chinese ancestors were Hokkien. My grandmother on my mother’s side for instance had a Spanish father and a Visayan mother, and she went on to marry my grandfather, who is Hokkien. These feelings are further complicated by the transnationalism of Filipino identities: how we talk about diasporic experiences and our relationships to colonialism and the land when we are abroad and at home, wherever that may be.

As a Filipino person, I find there is no single term, hyphenated or not, that can fully capture the layered richness of who I am, and who we all are. While Filipino is a broad word meant to encapsulate seven thousand islands and even more different experiences, I find comfort, belonging and home in the word Filipino, as it can sometimes be hard to fight for acceptance as someone living in the diaspora and being constantly met with the phrase ‘Filipino ka ba?’

At its core, Lunar New Year is about transitions: letting go of winter’s darkness and welcoming spring’s rebirth. When you layer in the Filipino concept of anito (ancestors) guarding and guiding us, the appearance of the snake in our ancestral beliefs is a good omen and is a time to stop and be open to spiritual insight. Personally, how I celebrate Lunar New Year as a Filipino Chinese Canadian is with the belief that we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, carrying their hopes and dreams into a new season.

This year’s card features a saying in four Chinese characters: 豐衣足蛇 ‘to live a life free of scarcity’. Traditionally, these sayings are a play on words, where the zodiac animal of the coming year replaces a similar sounding word in a classical idiom. In Romeo’s design, nestled between two peonies—symbols of prosperity and good fortune—the Snake embodies a boldness and trust that the New Year will bring these in abundance.

May your Lunar New Year be blessed with balance, harmony, and abundant possibility.

If you enjoyed reading this reflection, read last year’s reflection mythologies of the diasporic new year, with Triet Pham.

If you would like to learn more about the work hua foundation does, learn about how we started and where we’re headed in 2025.